Get access to the full report here!

Double materiality has become a familiar concept in sustainability and financial reporting. Yet for many banks, it still functions more like a narrative framework than a decision tool. Impact materiality is frequently described in broad terms, while financial materiality is handled separately through traditional risk lenses. The result is often a set of qualitative heatmaps or generic materiality scores that are difficult to translate into credit decisions, pricing, product design, or portfolio steering.

A more useful approach starts with a simple premise: the same natural-capital drivers can be material in two different ways—and each perspective requires its own valuation logic.

That is the premise behind the 2024 Natural Capital analysis conducted for ANSA McAL Banking Sector (covering ANSA Merchant Bank Limited; ANSA Bank Limited and ANSA Wealth Management Limited, hereafter referred to as the “bank”) for its activities in Trinidad. The work delivers an integrated view of Natural Capital impacts and Natural Capital risks across investments and loans, turning nature-related data into decision-ready insights that can support portfolio management, credit processes, and innovation.

This is not “reporting for reporting’s sake.” It is a practical demonstration of what happens when double materiality is treated as something that can be quantified, compared, and acted on.

One set of drivers, two valuation approaches: a quantitative way to do double materiality

Double materiality asks two questions:

- Inside-out (impact materiality): How do financed activities affect nature and society?

- Outside-in (financial materiality): How do nature-related shifts affect the bank and its clients?

Where many approaches stop at qualitative prioritisation, natural capital valuation goes further by applying two distinct valuation approaches to the same underlying drivers.

Take greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as an example:

- Under impact valuation, emissions are monetised based on their broader consequences—reflecting costs to society and ecosystems through climate impacts that affect health, livelihoods, and biodiversity.

- Under risk valuation, emissions are treated as an exposure that can translate into financial outcomes—through transition dynamics such as carbon pricing, changing regulation, evolving technology, and reliance on emissions-intensive inputs (e.g. fuel) or processes.

The same “driver” appears in both analyses, but it is measured through two different lenses. That dual valuation logic makes double materiality less subjective and more operational: instead of relying mainly on stakeholder opinions or generic materiality databases, the bank gains a quantitative basis for prioritisation and action.

Positioning nature as a performance lens

The bank sits at the centre of trade, enterprise activity, and household finance. That position comes with a wide footprint across sectors—meaning the portfolio both influences and depends on natural systems, from water and land to climate stability.

In its sustainability journey, the bank has signalled a clear ambition: to move beyond high-level commitments and establish a measurement foundation that makes nature visible inside decision-making. The 2024 work reflects that intent by building a baseline for impacts and risks—an essential step if natural capital is to become more than an annual disclosure exercise.

Just as importantly, it reinforces a forward-looking posture: treating natural capital not as a compliance topic, but as a strategic lens for resilience, risk quality, and long-term value creation—especially as climate and nature-related risks become more financially material across the real economy.

What was done: portfolio analysis, methodology, and the “impact-and-risk” bridge

The 2024 analysis examined the bank’s Trinidad and Tobago portfolios across investments and lending and quantified a set of natural-capital drivers that go beyond carbon, including (among others) climate change, land use, pollution-related impacts, and resource use.

Three methodological features matter for financial institutions considering how to make this work actionable:

1) Breadth beyond carbon—without losing finance-grade structure

Natural capital was assessed across multiple drivers rather than focusing narrowly on financed emissions. This matters because different sectors can be dominated by different impact types (for example land use versus climate), and because climate-only approaches can miss material pressures embedded in supply chains and operating models.

2) Finance-aligned modelling that supports comparability

An input-output approach was used to model most financed activities in a way that supports portfolio-wide comparability. Where asset classes required greater specificity, more tailored methods were applied (for example life cycle-based modelling for vehicle-related impacts).

3) A dedicated risk valuation method that values the same drivers through a business lens

A core addition in this work is the integration of a risk valuation approach (developed by Valuing Impact) designed to assess the same natural-capital drivers through a business valuation process—converting nature-related dependencies and pressures into financially relevant risk severity signals.

In practice, that means taking nature-related drivers (like flood exposure, resource dependency, or temperature stress) and translating them into a structured view of how they can affect business performance—through:

- operational disruption and downtime,

- changes in input availability and cost,

- potential capex requirements for adaptation,

- changes in customer demand or asset values,

- and broader transition dynamics.

This “impact-and-risk bridge” is what makes the results particularly useful for portfolio management: it links environmental drivers not only to societal cost, but also to potential financial outcomes—creating a shared language between sustainability teams, risk functions, and product leaders.

Key findings: impacts concentrate in a few sectors—and intensity tells you where to act

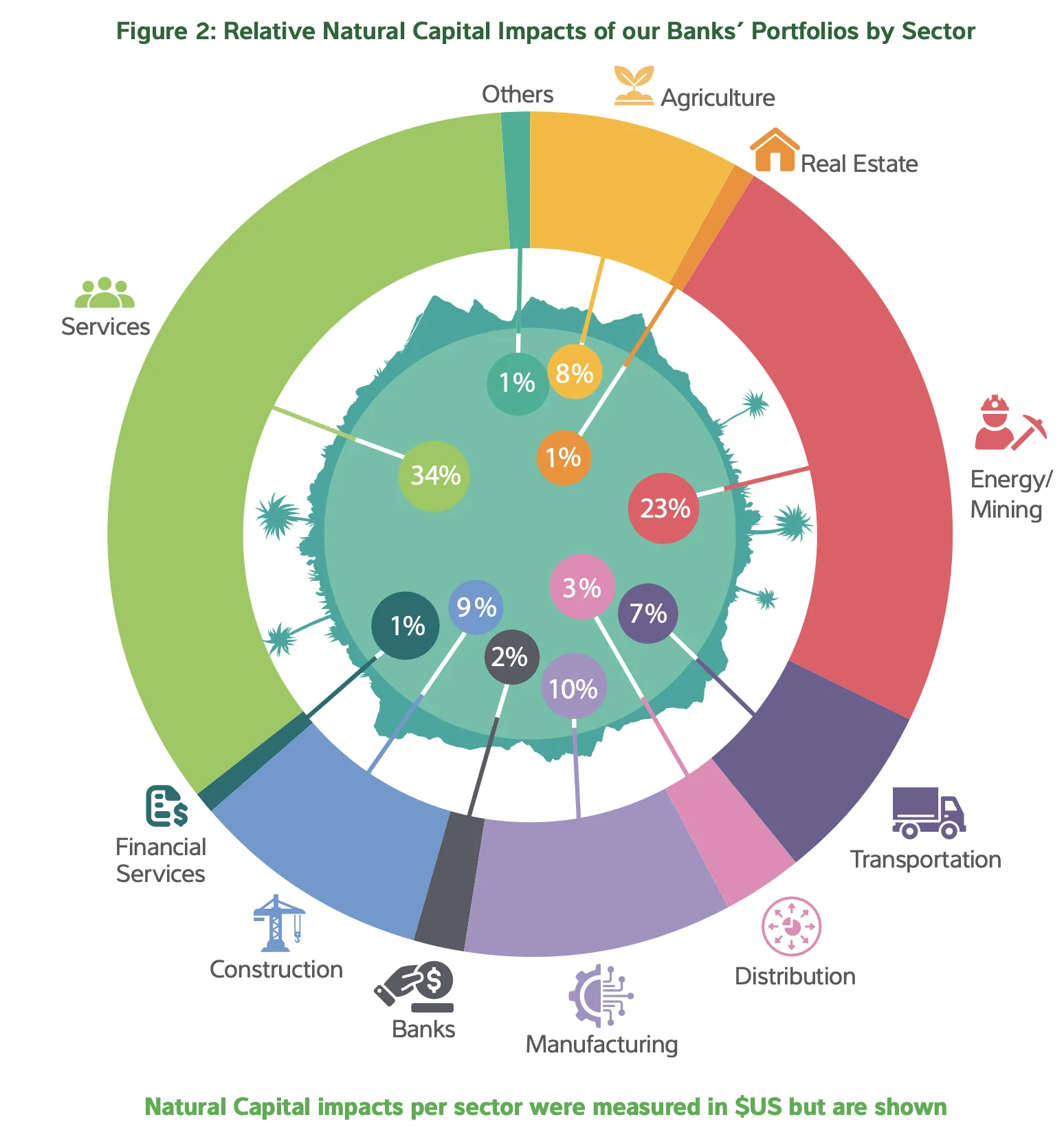

One of the clearest outputs is the sector view. Across the Trinidad portfolio, six sectors stand out in terms of monetised natural-capital impacts: Services, Energy/Mining, Manufacturing, Construction, Agriculture, and Transportation.

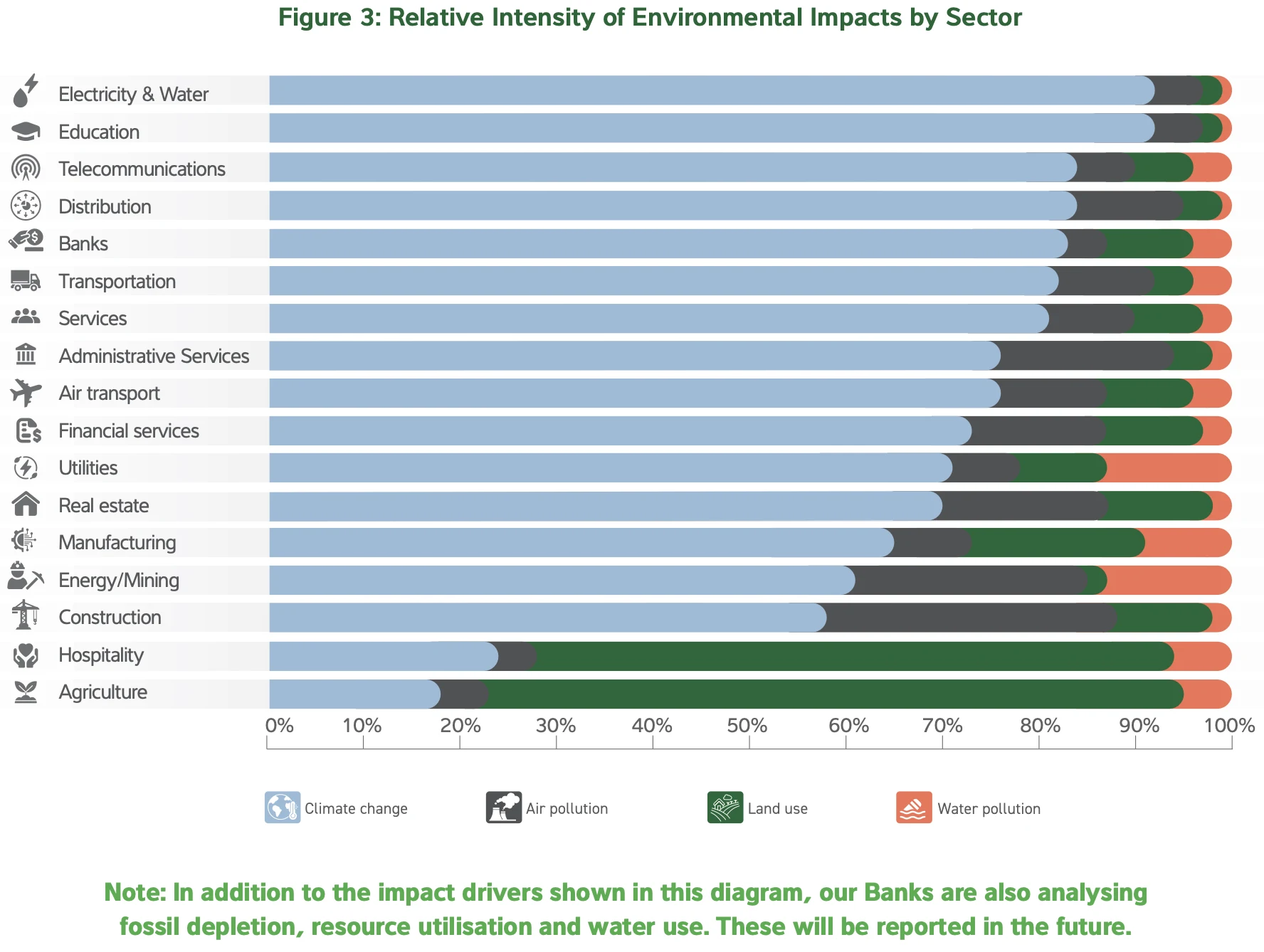

When impacts are consolidated across portfolios, climate change is the dominant driver overall, accounting for the largest share of impacts. But the more useful insight emerges when the analysis shifts from “portfolio totals” to “sector intensity.”

Impact intensity varies sharply across sectors. The analysis shows that while climate change is the leading driver overall, it is not the leading driver everywhere. In particular, agriculture and hospitality/tourism display land-use impacts as the most material pressure.

This is a practical difference from many traditional materiality approaches. A conventional matrix may list “climate” and “biodiversity” as material topics across the board, but it often fails to show where the portfolio is specifically land-use driven versus emissions-driven—yet that distinction should change what the bank ask clients to do, which KPIs matter, and which financing solutions will have the greatest effect.

A second example illustrates why multi-driver natural capital analysis is valuable for product design: vehicle-loan emissions may represent a relatively small portion of total climate impact, but when other environmental impact types associated with transportation are included (pollution and resource-related pressures), the integrated contribution becomes more meaningful. In other words, what looks minor through a carbon-only lens can become strategically relevant through a natural-capital lens—especially if the bank is considering product features, incentives, or eligibility criteria tied to environmental performance.

Translating impacts into risk: physical risk dominates—and flood exposure becomes visible in the portfolio

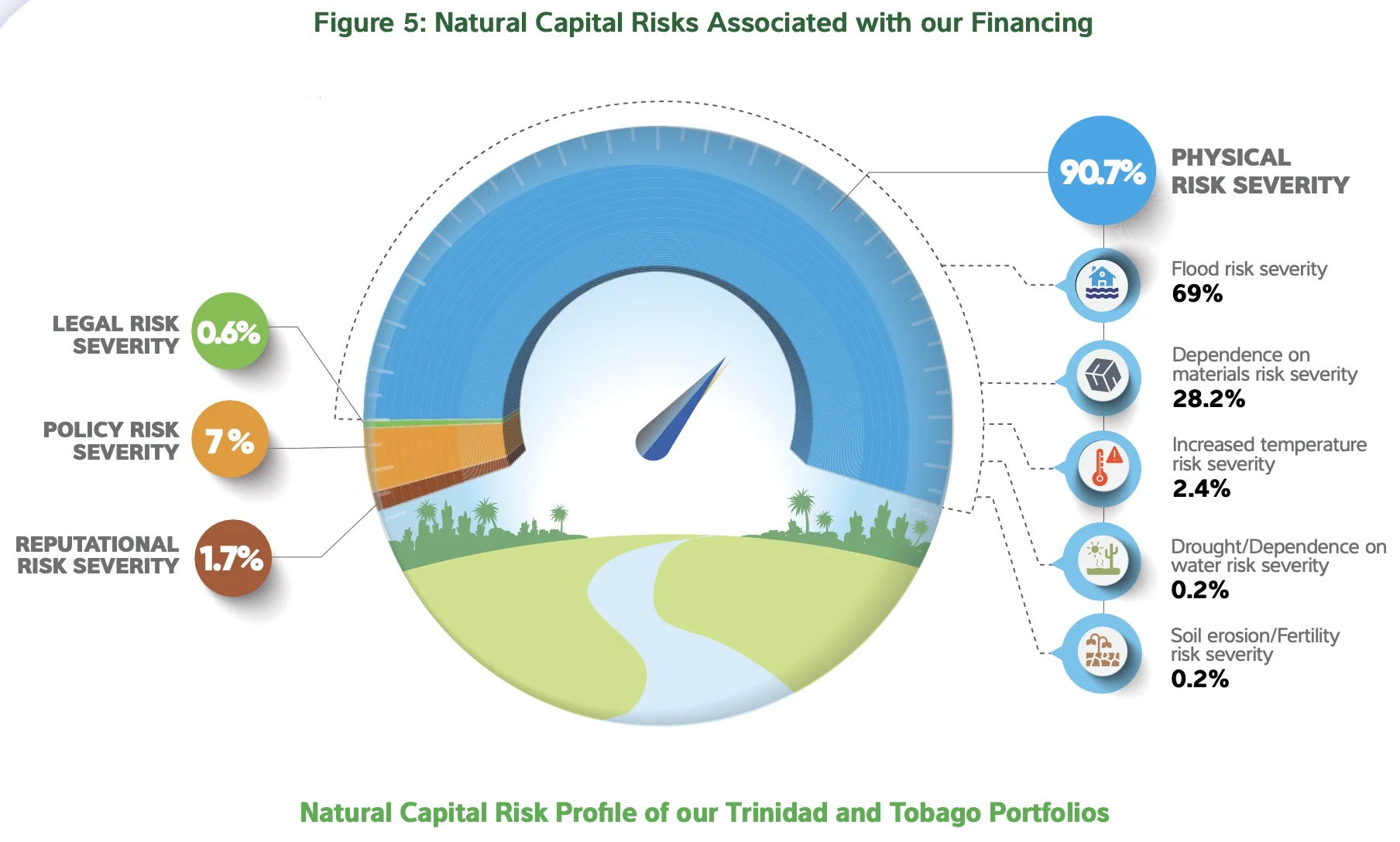

On the risk side, the results are decisive: physical risks dominate the overall natural-capital risk profile, representing 90.7% of total risk severity.

Within that physical-risk picture, one driver towers above the rest: flood risk, representing 69% of physical risk severity.

The next most significant component captured in the figure is dependence on materials (28.2% risk severity), followed by increased temperature risk (2.4%), and smaller contributions from drought/water dependence and soil erosion/fertility pressures (each 0.2%). This breakdown matters because it clarifies where risk teams and portfolio managers can focus first: it’s not only “climate risk in general,” but a specific profile that points to hazards (flooding), dependencies (materials), and stressors (temperature).

Crucially, the risk valuation is not left at a conceptual level. The analysis paid special attention to the bank’s mortgage portfolio exposure to flooding, using flood susceptibility data to assess the current exposure of mortgaged properties. That is exactly the kind of translation banks need if nature-related risk is to influence underwriting, collateral policy, and portfolio monitoring.

Why these insights are immediately usable: credit processes, engagement, and innovation

Quantified natural capital outputs become valuable when they map onto the decisions banks already make. This work supports several of the highest-leverage use cases:

1) Updating credit risk and portfolio steering

A quantified risk profile can strengthen credit risk rating in two ways:

- Hazard-specific differentiation: rather than treating “physical risk” as a generic factor, flood susceptibility can be embedded into mortgage and commercial property considerations, supporting better-informed decisioning and monitoring.

- Sector and dependency nuance: resource- and dependency-related risks (like materials dependence) can become part of how the bank evaluates resilience in certain business models, particularly where supply chain and input security matter.

The practical outcome is not simply “more ESG data,” but better discrimination: which exposures are robust under stress, and which are fragile without adaptation.

2) Better client communication and engagement—grounded in drivers, not slogans

Clients often hear broad requests: “decarbonise,” “improve sustainability,” “report more metrics.” A natural-capital lens makes engagement more specific:

- If land use dominates a sector’s impact intensity, the conversation should focus on land management practices and measurable improvements.

- If flood risk is a leading financial threat, engagement should focus on resilience actions, site selection, protective investments, and continuity planning.

This is a meaningful upgrade from generic ESG questionnaires because it connects the “ask” to quantified drivers that matter for both impact and risk.

3) Product innovation that aligns incentives with real-world outcomes

The results create a stronger foundation for product innovation because they clarify where impacts and risks concentrate—particularly around flooding, extreme heat, and dependence on energy and materials—and therefore where finance can most effectively reduce both risk and harm. One practical direction is to introduce loans with a small interest-rate discount when clients can show progress against a short set of relevant indicators, using evidence they already have (like utility bills, production logs, invoices, or photos).

This enables the bank to:

- reward verified improvements in the most material drivers (not only carbon), by focusing on a clear menu of outcomes such as energy and emissions, water and land use, and materials/circularity,

- support resilience-building in the places where physical risk is dominant, by nudging practical measures alongside finance (for example, upgrades that reduce heat stress or flood disruption),

- turn outcomes into learning, tracking whether these “improvers” perform better over time and using that feedback to refine credit approach and product design.

In that sense, natural capital valuation becomes a product strategy tool: it highlights not only where exposure exists, but where the best opportunities for positive impact and resilience-building are likely to be found.

How this breaks from traditional double materiality—and why it can improve performance

Traditional double materiality assessments are often good at producing priorities, but weaker at producing decisions. They tell you what matters; they rarely tell you:

- how big the exposure is,

- which drivers dominate by sector,

- where the most actionable levers sit,

- and how impacts and risks connect to products, pricing, and portfolio steering.

A quantified natural-capital approach changes that by:

- using the same drivers for both impact and risk, while applying distinct valuation logics aligned to inside-out and outside-in perspectives,

- revealing sector-specific intensity that reshapes prioritisation (climate overall, land use for key sectors like agriculture and hospitality),

- and translating nature risk into a profile that can be operationalised (physical risk dominance, flood risk prominence, and specific dependency and temperature stresses).

For banks, the added value is straightforward: better risk quality, clearer strategy, and more credible innovation—because the environmental lens is anchored in measurable drivers and linked to financial decision points.

Get access to the full report here!