There are now over a dozen sources of value factors and impact valuation methods — yet no single directory or decision framework exists. This guide maps the full landscape and helps practitioners choose the right source for their specific application.

Download the guide

A fragmented field

If you have ever tried to monetize the social or environmental impact of a business, an investment fund, or a public program, you have faced a deceptively simple question: where do I get my value factors?

Value factors are the coefficients that translate physical and social metrics — tonnes of CO₂, hours of education, cases of respiratory illness — into monetary or well-being units. They are the backbone of any impact valuation. Yet the field has grown organically over fifteen years, and today at least fourteen credible sources compete for attention, each with different scope, valuation philosophy, regional coverage, and price tag.

The result is that practitioners default to whatever source they discovered first, or mix sources without realizing that different valuation approaches answer fundamentally different questions. This article offers a structured map: we catalogue the main sources, score them against transparent criteria, and match them to five practical applications.

What are value factors, and why does the source matter?

A value factor expresses the relative importance of a change in natural, human, social, or economic capital — typically as a price per unit of impact. Crucially, the number you get depends on the valuation approach behind it:

- Damage cost (welfare-based) — the societal cost of harm caused, typically grounded in welfare economics and willingness-to-pay studies. This is the core approach behind CE Delft, UBA, and S&P/Trucost.

- Remediation/solution cost — the cost to remediate the damage, restore the affected capital, or meet policy targets and social thresholds (e.g., living wage). True Price and Impact Institute bases its method on this approach, combining it with damage costs.

- Damage cost + solution cost + economic multiplier — several sources (GIST, WifOR, IFVI/Capitals Coalition) blend damage and solution costs with economic multipliers to capture indirect economic effects across multiple capitals.

- Well-being — impact measured as changes in quality-adjusted or wellbeing-adjusted life years (QALYs, WELLBYs, WALYs, eQALYs). These approaches keep people — not dollars — as the unit of account, though they can be monetized.

- Stakeholder-defined proxies — financial approximations chosen through engagement with affected communities, as in Social Return on Investment (SROI).

A damage-cost factor for water pollution and a restoration-cost factor for the same pollutant will produce different numbers, because they answer different questions. Neither is wrong — but mixing them in the same impact statement without acknowledging the difference erodes credibility.

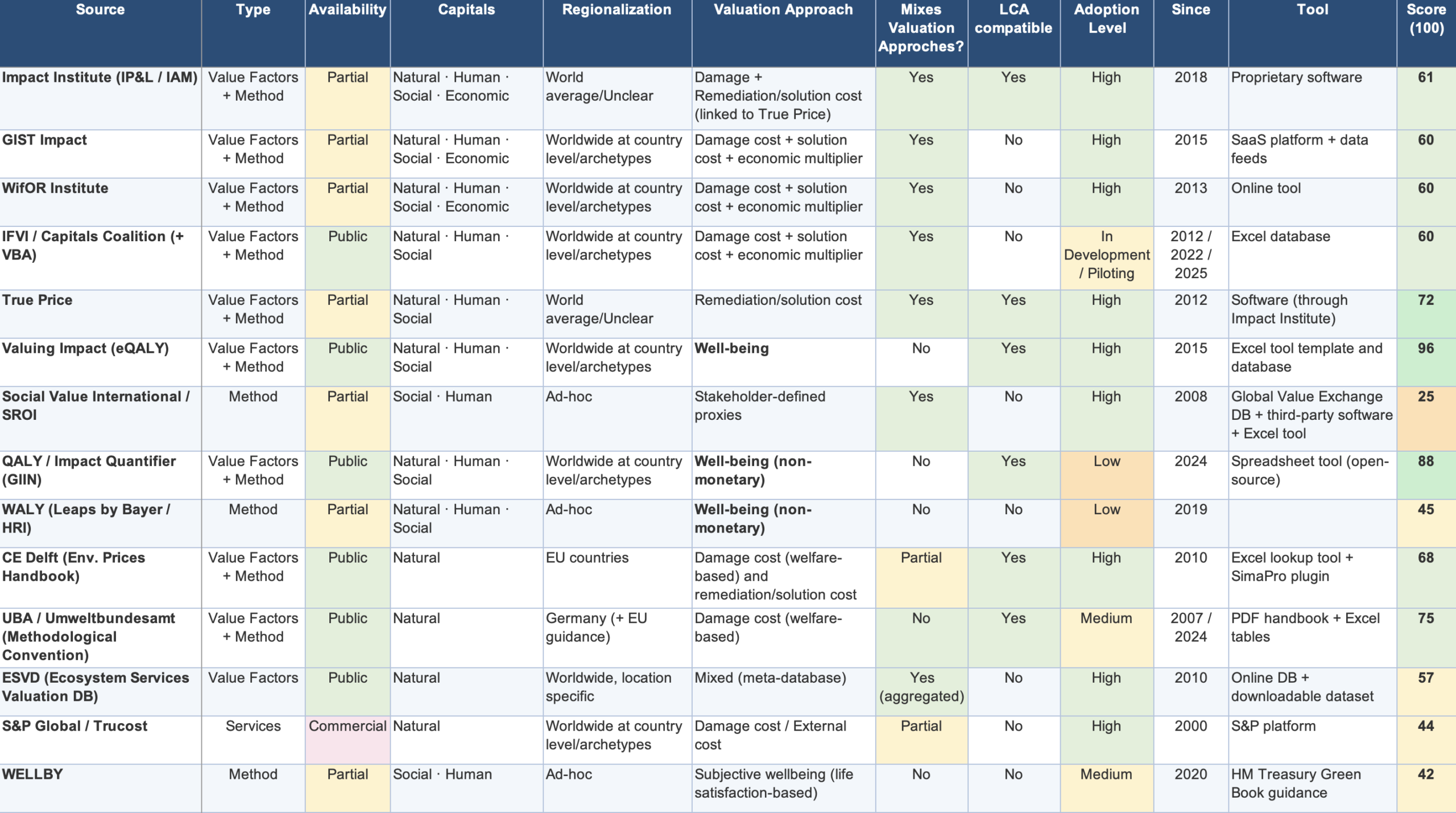

The current landscape at a glance

Figure 1 below presents the fourteen sources we identified, organized by the type of offering (value factors, method, or full service), the capitals they cover, their geographic scope, and valuation approach. Availability is color-coded: green for fully public, yellow for partially available, and red for commercial-only.

A few patterns emerge immediately. The broadest coverage of all four capitals comes from the service providers (Impact Institute, GIST, WifOR) — but their factors are only partially public. Public availability and multi-capital coverage together narrow the field to IFVI, True Price, eQALY, and the GIIN Impact Quantifier. Meanwhile, LCA compatibility — essential for anyone connecting impact valuation to product-level footprints — is limited to CE Delft, True Price, eQALY, and the GIIN tool.

Scoring the sources: a transparent comparison

To move beyond qualitative impressions, we scored all fourteen sources against six weighted criteria. The scoring logic is deliberately transparent — readers can disagree with a weight and re-run their own ranking. The full detailed scoring is available in the companion spreadsheet for download alongside this article.

Scoring methodology– Each source was rated on six criteria, weighted to reflect what matters most in practice:

- VF Availability (20 pts) — Are the value factors publicly accessible, partially available, or fully proprietary?

- Capitals breadth (20 pts) — How many of the four capitals (Natural, Human, Social, Economic) does the source cover?

- Regionalization (20 pts) — Does the source provide region- or country-specific factors, or only global averages?

- Valuation consistency (20 pts) — Does the source use a single coherent valuation approach, or does it mix damage costs, restoration costs, and economic multipliers?

- Adoption (10 pts) — How widely is the source used by practitioners, institutions, or standard-setters?

- LCA compatibility (10 pts) — Can the factors be linked to Life Cycle Inventory databases (e.g., ecoinvent) for product-level footprinting?

The four highest-weighted criteria (20 pts each) reflect the attributes that most determine whether a source can be used rigorously and independently: access to the actual factors, breadth of coverage, geographic granularity, and methodological coherence. Adoption and LCA compatibility carry lower weight (10 pts each) because they are more context-dependent — critical for some applications, irrelevant for others. The final scores shown in Figure 1 are the sum across all six criteria, out of a maximum of 100 points.

What the score reveals

The scoring reveals a clear separation into three tiers. The well-being methods (eQALY, GIIN Impact Quantifier) rank highest, primarily because their single, unified valuation approach earns the full twenty points for consistency — a criterion where most monetary methods lose ground due to mixing damage costs with restoration costs or economic multipliers within the same framework. This methodological coherence is not just an academic preference: it is what makes cross-topic and cross-fund comparisons meaningful.

CE Delft scores well on the strength of its deep substance coverage (over 3,000 environmental prices), full public availability, and strong regionalization, even though it only covers natural capital. True Price, Impact Institute and IFVI/CapsCo occupy the middle tier, each balancing broad capital coverage against partial availability or incomplete consistency. The commercial service providers (GIST, WifOR, Impact Institute) offer impressive breadth but score lower on availability and consistency because their factors are only partially public and often blend multiple valuation approaches.

At the other end, SROI scores lower on these particular criteria precisely because its strength — stakeholder-defined, context-specific valuation — works against standardization and replicability. This is not a flaw; it is a design choice suited to a fundamentally different application where community voice matters more than cross-study comparability.

It is worth emphasizing that the weights themselves embed a perspective. A practitioner who values adoption above all else, or who works exclusively in policy appraisal, might assign very different weights — and reach a different ranking. We encourage readers to download the spreadsheet, adjust the weights, and see how the ranking shifts.

Which brings us to the central point: no single source is best for all purposes.

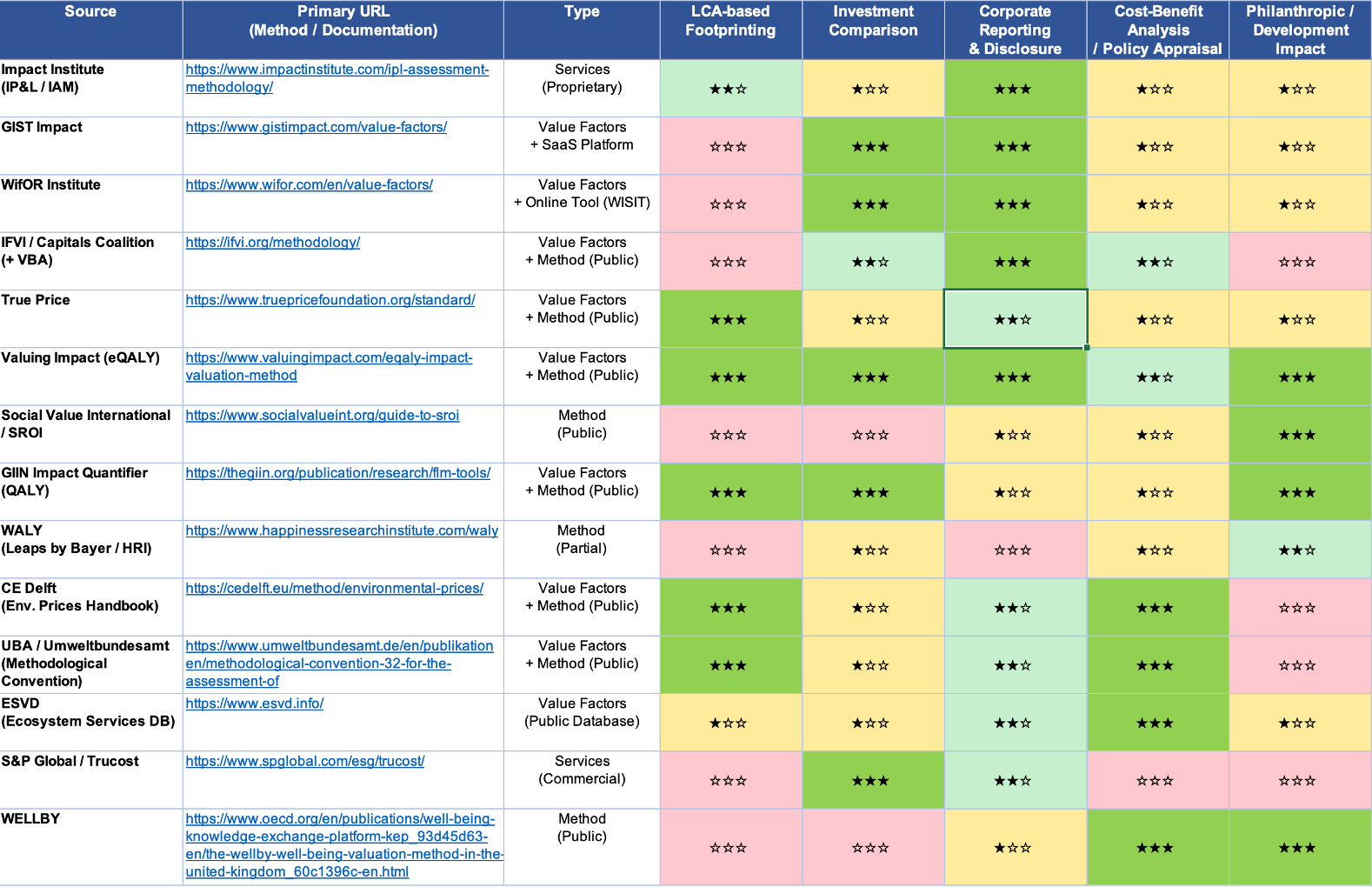

Matching method to purpose: five practical use cases

Rather than picking one “winner,” practitioners should start with the question: what decision does this valuation need to support? Figure 2 rates each source’s suitability across five common applications.

Let us unpack each column

LCA-Based footprinting

Connecting impact valuation to Life Cycle Assessment requires value factors expressed per substance or per environmental flow, compatible with LCI databases like ecoinvent. CE Delft leads here with over 3,000 substance-level environmental prices and a SimaPro plug-in. UBA’s Methodological Convention 3.1 follows a similar structure, providing damage-cost factors per pollutant that can be mapped to LCI flows — making it a strong complement to CE Delft for German and EU contexts. True Price built its method on LCA principles and provides monetization factors for ten environmental and ten social impacts. The eQALY method explicitly builds on LCA inventory data and covers nineteen environmental drivers, while the GIIN Impact Quantifier routes environmental impacts through LCA as well. Sources that operate at the sector or company level without per-substance factors — such as GIST, WifOR, and S&P/Trucost — are a poor fit for this application.

Investment comparison and portfolio screening

When comparing investments or funds, the cardinal requirement is a single, consistent valuation technique applied across all capitals. If one fund’s carbon impact is valued using damage costs while another’s is valued using abatement costs, any comparison is meaningless. This favors sources that do not mix methods: eQALY (well-being throughout), the GIIN Impact Quantifier (QALYs), and S&P/Trucost (damage-cost throughout). The commercial multi-capital platforms GIST and WifOR also serve this use case well by offering pre-computed results across large universes of companies, though their blending of valuation approaches means cross-platform comparisons should be handled with care. IFVI’s damage-cost approach also works here, though its social capital methodology is still under development.

Corporate reporting and disclosure

For voluntary sustainability reporting or alignment with emerging disclosure frameworks (ESRS, IFRS S1/S2), the requirements are less strict on methodological purity but more demanding on breadth of capitals and institutional credibility. This is the most permissive column in our table: most sources score at least ★★☆, because the reporting context tolerates mixed methods as long as they are transparently disclosed. The strongest fits combine broad capital coverage with high adoption and alignment with recognized frameworks — IFVI stands out here through its explicit alignment with IFRS sustainability standards and the recent merger with the Capitals Coalition, while the Impact Institute and GIST offer ready-made multi-capital impact statements suited to integrated reporting.

Cost-benefit analysis and policy appraisal

Government-commissioned Social Cost-Benefit Analysis requires welfare-based damage costs, ideally endorsed by public institutions. CE Delft’s Environmental Prices Handbook is the de facto standard for SCBA in the Netherlands and increasingly across the EU, while UBA’s Methodological Convention 3.1 serves the same role in Germany — together, these two sources anchor environmental cost estimation in European policy appraisal. The ESVD provides location-specific ecosystem service values widely used in land-use policy. WELLBY, endorsed by HM Treasury’s Green Book, is the leading method for monetizing well-being outcomes in UK policy appraisal. Sources with rights-based or stakeholder-defined approaches are a weaker match because they do not produce welfare-economic estimates in the strict CBA sense.

Philanthropic and development impact

Foundations, development agencies, and impact investors evaluating grants or programs need methods that center human well-being. This is where the well-being family shines: eQALY translates over thirty impact drivers into a single well-being metric, the GIIN Impact Quantifier was designed for fund-level comparison in developing countries, and WELLBY provides a simple, monetizable unit backed by subjective-wellbeing research. SROI remains relevant because stakeholder engagement is intrinsically valuable in development contexts, even though its bespoke nature limits comparability. WALY, though less widely adopted, offers an interesting approach for health- and agriculture-focused interventions.

Key trade-offs and combining sources responsibly

Several tensions cut across all five applications. No source resolves all of them at once — each practitioner must decide which trade-off matters most for the decision at hand.

- Monetary vs. non-monetary units. QALYs, WALYs, and eQALYs keep people as the unit of account, avoiding the ethical discomfort of pricing a human life. But some stakeholders — boards, regulators, finance teams — need a dollar figure. The eQALY method bridges this gap by defining a unified well-being indicator that can still be expressed in monetary terms when needed. Practitioners should be explicit about which unit they are reporting and why.

- Consistency vs. coverage. A single-method source produces internally comparable results but may not cover every impact topic or capital. A multi-method source covers more ground, at the cost of internal comparability. For example, GIST and WifOR span all four capitals but blend damage costs with economic multipliers, while CE Delft maintains strict methodological consistency but is limited to natural capital.

- Public vs. proprietary. Open-access factors (CE Delft, UBA, eQALY) enable scrutiny, replication, and customization. Commercial platforms (S&P/Trucost, GIST, WifOR) offer convenience, pre-computed company-level results, and analytics — but at the cost of transparency and the ability to audit the underlying assumptions.

- Granularity vs. ease of use. Substance-level sources like CE Delft require LCA expertise to deploy correctly, while sector-level platforms can be applied quickly but may miss product-specific nuances. The right level of granularity depends on whether the goal is a detailed footprint or a portfolio-wide screening.

- Regional precision vs. global applicability. Some sources provide country- or region-specific factors (CE Delft, UBA, ESVD), while others use global averages or offer limited regionalization. For projects in specific geographies — particularly in the Global South — the availability of localized factors can be a deciding criterion.

Valuation is not impact modeling

It is worth pausing to clarify what value factors do — and what they do not do. The sources reviewed in this article address the valuation step: translating a measured impact indicator (tonnes of CO₂, years of education, cases of disease) into a monetary or well-being unit. They answer the question “what is this impact worth?”

But before you can apply a value factor, you need the impact indicator itself. That is the domain of impact modeling — the upstream work of quantifying what changed and by how much.

Impact modeling draws on an entirely different set of methodologies and data sources:

- Environmental impacts: carbon accounting frameworks (GHG Protocol), Life Cycle Assessment (ISO 14040/44), water footprinting (ISO 14046), biodiversity assessments (TNFD, SBTN)

- Health and well-being: epidemiological dose-response models, life satisfaction surveys, DALY calculations, health burden studies

- Education and skills: learning outcome measurement, years of schooling equivalents, skills assessments

- Economic outcomes: income change measurement, employment tracking, purchasing power adjustments, economic multiplier models

- Social outcomes: housing quality indices, access-to-services metrics, social cohesion surveys

No value factor source replaces these modeling efforts. A damage-cost coefficient for PM₂.₅ is useless without a reliable estimate of how many micrograms of PM₂.₅ a given activity actually emits. Similarly, a well-being weight for education means nothing without data on how many additional years of schooling a program actually delivered.

Practitioners should therefore think of impact valuation as a two-stage process: first model the impact (using the appropriate accounting, measurement, or survey methodology), then value it (using the sources compared in this article). Conflating the two stages — or assuming that a value factor source also solves the measurement challenge — is a common source of error.

Consider waste as a concrete example. Measuring the impact of waste requires modeling the physical fate of materials through different treatment pathways — landfill, recycling, incineration, composting, littering — each of which produces a distinct environmental profile. This is an impact modeling exercise that depends on waste composition data, treatment technology parameters, and local infrastructure. Only once these pathways have been modeled and translated into environmental indicators (CO₂ emissions, land use, water pollution, resource depletion) can value factors be applied to monetize or weight the results. The value factor tells you what a tonne of CO₂ or a hectare of land use is worth — it does not tell you how much CO₂ a landfill actually emits. Getting the modeling right is at least as important as choosing the right value factor.

Combining sources: two guardrails

There are situations where combining sources is justified — for example, using ESVD data to fill a biodiversity gap in a primarily damage-cost valuation, or using CE Delft factors for environmental substances alongside a well-being method for social impacts.

But practitioners should follow two guardrails:

- Disclose the mix. Never aggregate values across different valuation approaches without clearly stating which method was used for which impact. Readers need to know whether the numbers in a single report are comparable or not.

- Do not mix incompatible approaches for the same impact. Combining damage cost and restoration cost for the same impact driver (e.g., water pollution) in a single headline number is methodologically incoherent — the two approaches answer different questions and will produce different magnitudes.

Where the field is heading

The landscape is consolidating. In 2025, the Capitals Coalition completed its strategic merger with IFVI and formed a partnership with the Value Balancing Alliance to standardize impact accounting methodology. GIST Impact and WifOR Institute jointly published value factors for twenty-five countries. The EU’s E-GAAP project is working toward generally accepted environmental accounting principles. And the well-being approach is gaining institutional momentum: HM Treasury and the New Zealand Treasury have both adopted WELLBY-based guidance, while the GIIN Impact Quantifier is bringing QALY-based thinking into mainstream impact investing for the first time.

These convergence efforts will not eliminate the diversity of methods — nor should they. Different questions require different tools. But they will increasingly make it possible for practitioners to choose a source based on fitness for purpose, rather than on whatever they happened to find first.

Beyond societal value: the missing link to business decisions

There is, however, a significant gap that none of the sources reviewed in this article fully address. Nearly all current value factor methods — whether damage cost, restoration cost, or well-being — estimate societal or economic value: the cost to society of a tonne of CO₂, the welfare loss from air pollution, the well-being gain from education. This is essential for understanding impact at the macro level, but it leaves a critical question unanswered for corporate decision-makers: what does this impact mean for my business?

Translating societal impact into risk exposure, commercial opportunity, cost of action or business value requires an entirely different set of valuation lenses. What is the financial risk of continued dependence on high-emission inputs? What revenue upside comes from solving a social problem? What would it actually cost to eliminate a negative impact? These questions demand methodologies that go beyond societal damage costs — linking impact to P&L-relevant metrics like avoided costs, future revenue at risk, reputational value, or solution investment requirements. As explored in Impact Valuation Lenses — Or How Not to Get Impact Valuation Wrong, applying a single valuation perspective to all decision contexts is precisely how organizations get impact valuation wrong.

The most powerful insight comes from using multiple valuation perspectives in parallel — not by mixing them into a single number, but by keeping each lens consistent and comparing the results side by side. A societal damage cost, a risk-adjusted business exposure, and a solution cost estimate for the same impact driver will yield very different numbers, and that divergence is itself informative. It reveals where societal urgency and business incentives are aligned, where they diverge, and where intervention is most cost-effective. Frameworks like the ROImpact Canvas are emerging to bridge this gap, systematically connecting impact valuation to business strategy by mapping societal impacts onto financial levers.

This multi-lens approach represents the next frontier for the field: not replacing societal value factors, but complementing them with risk, opportunity, and solution-cost perspectives that make impact valuation actionable in boardrooms — not just in sustainability reports.

The companion comparison spreadsheet is available for download. We invite practitioners to use it, challenge the scores, and share their experience — the field advances when knowledge is pooled, not hoarded.

About this research

The comparison table and application guide were compiled in February 2026 based on publicly available documentation from the Capitals Coalition, IFVI, VBA, GIIN, CE Delft, ESVD, GIST Impact, WifOR Institute, S&P/Trucost, Social Value International, True Price, Impact Institute, Leaps by Bayer, the Happiness Research Institute, HM Treasury, and academic publications. The scoring methodology is transparent and documented in the downloadable spreadsheet.

Suggestions and corrections are welcome.